THE LOST WORLD: ECHOES OF TRADITIONAL LITHUANIAN JEWISH ART

"The Lost World" is an exhibition in memory of the Jewish culture, once prosperous in Lithuania. Almost all of the Lithuanian Jewish community, its centuries-old cultural treasure, which has glorified the name of Lithuania in the world, and its artistic and architectural heritage, were brutally destroyed during the Nazi invasion. The exhibition presents saved and preserved objects of Lithuanian Jewish heritage – deep-rooted traditional Jewish art and 19th century-born and ever-developing secular art of the Lithuanian Jews.

The Lithuanian Jews, the litvaks, stood out among the other Jews for strict preservation of the religious tradition, intellectual rationality, special education, and for certain features of their religious and everyday life. All this influenced a specific artistic expression. It was until the second part of the 19th century that only traditional art developed in the Jewish culture of Lithuania, limited by old traditions. It was mostly expressed in the synagogue architecture, interior design and decorations, creation of ritual objects or the illustrations and decorative motifs used in religious texts. The traditional Lithuanian Jewish art is notable for its synthesis of craft and spiritual doctrine.

The mode of life of the Lithuanian Jews, determined by the religious regulations and rituals, is revealed through the exhibited items, which are associated with the interior decoration of synagogues, and ritual objects, which are designed for the rites performed at the synagogue and at home, and for the main holidays of the year and life cycle.

The following elements of the interior of the Vilnius Great synagogue are key to the exhibition: the twofold doors of the aron kodesh, the cartouche with the Tablets of the Law, which used to decorate the topmost level of the aron kodesh, and the candlestick from the omed (the cantor’s desk), which stood in front of it. These objects are all that is left of the Vilnius Great synagogue, built in the end of the XVI c. – the beginning of the XVII c., which had for centuries been the main spiritual axis of the Jewish community. The Great synagogue was also renowned for its ornate interior, which was considered one of the finest in the country. That interior with the gorgeous aron kodesh and the remaining objects, exhibited in our exposition, was immortalized in a watercolor by the world-famous artist Marc Chagall, who visited Vilnius in 1935.

The Great Synagogue of Vilnius (1573–1944) |

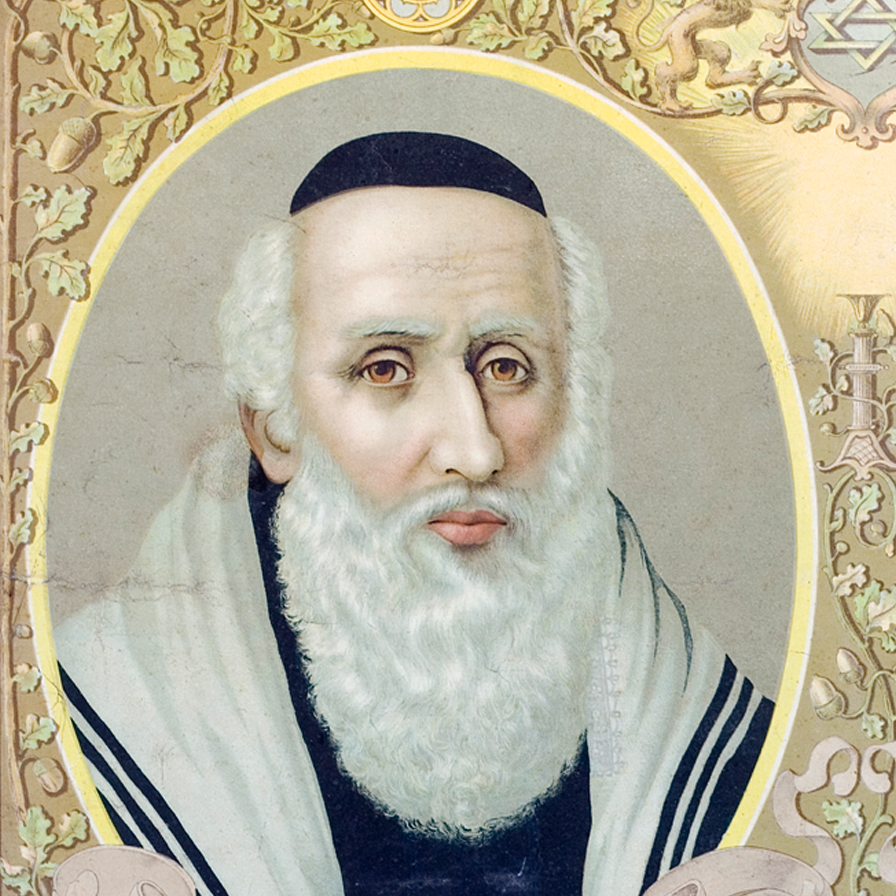

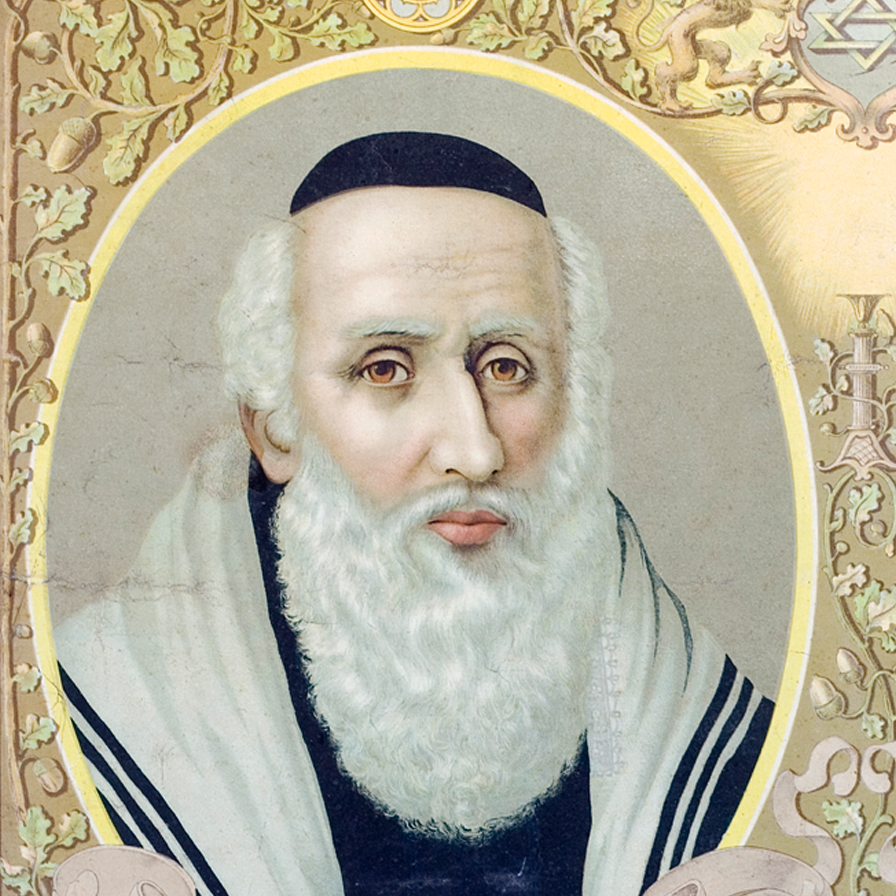

| The religious traditions of the Jewish people inLithuania are age-old. Many famous rabbis, cantors, Torah and Talmud scholars trace their origins here. Over centuries, important yeshivas and synagogues functioned in the country. During the XVI-XVIII a rich, distinctive synagogue architecture in wood as well as brick developed in the Grand Duchy of Lithuania. At the end of the XIX century, the number of synagogues in Vilnius alone exceeded one hundred. The oldest and most notable among them was the Great Synagogue of Vilnius, which attracted scholars of Judaism and Jewish tradition throughout Europe. The renown of Gaon Eiyahu Ben Shlomo Zalman, the most eminent figure in Jewish thought and in Torah and Talmud interpretation of the XVIII century created a reference to Vilnius as the Jerusalem of Lithuania. The Great Synagogue became the symbol of such status.

Vilniaus Gaonas Elijahu ben Šlomon Zalman

(1720–1797)

Constructed at the turn of the XVI – XVII centuries, the edifice survived several attacks and fires. It was heavily damaged during World War II and demolished in the post-war years. The majestic edifice which had brought fame to the city over centuries disappeared from its architectural ensemble.

Juozas Kamarauskas. Senoji Vilniaus Sinagoga 1899 m.

Testimony of its decorative and luxurious interior remains only in a small number of photographs and water-colors. Such valuable iconographic material, on display in the Museum, provides an intimation of its former grandeur.Three original details have survived: a cartouche with precepts of the Lord from the aron kodesh of the Synagogue, a candlestick with a decorative vertical shield from the cantor’s table, and a two-sided door from the aron kodesh.

These three objects of inestimable value make up the core of the present exhibition.

Kartušas su Dievo Įstatymo plokštėmis

Kantoriaus piupitro žvakidė

Aron kodešo durelės All other items in the exhibition, although never actually used in the Great Synagogue, serve to recreate its former devotional atmosphere. After the closing of the Jewish Museum in 1949, these objects were scattered throughout various museums in Lithuania (ethnography, history of religion, and art). In 1990 they were reassembled in the reopened Jewish Museum.

Kantoriaus piupitro skydas

Rinonimai – dekoratyvios Toros ritinių ašių viršūnės

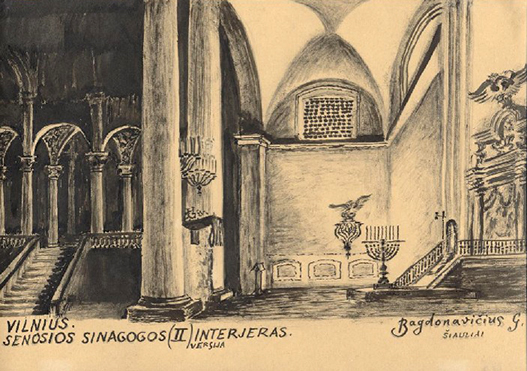

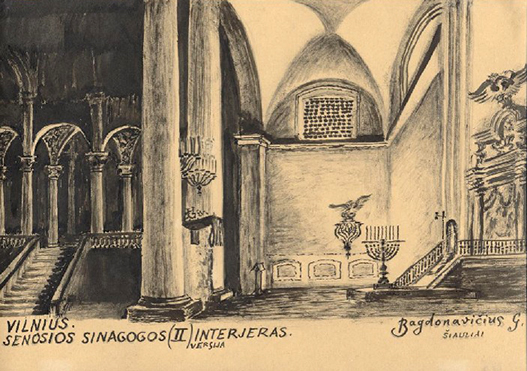

Religious objects from former Lithuanian synagogues form part of the history of traditional Jewish art in the country. Together with surviving iconographic material they demonstrate the extent of Jewish religious activity throughout the country prior to World War II. Even small towns had their synagogues. The majority of them were built of wood. Their distinctive architecture and decorative features exhibit the specific traditions of Jewish folk art which had developed throughout the Grand Duchy of Lithuania. Unfortunately only a small part of their formerly vast number still stand. They decay unattended. Most, like the Great Synagogue of Vilnius, remain only in photographs. Their black and white representations provide some indication of the former interiors. The exhibition includes drawings by G. Bagdonavicius of Siauliai who in the decade 1930-1940 immortalized many of them, including the Great Synagogue of Vilnius.

Gerardas Bagdonavičius. Vilnius. Senosios sinagogos interjeras.

Apie 1935 m. (iš Šiaulių Aušros muziejaus rinkinio).

The surviving pictures provide only a fragmentary representation of a rich past. Taken together, they intimate the richness of traditional Jewish art of Lithuania at the time. They provide not only specific details but also a basis for reconstitution of the spiritual environment in the Great Synagogue of Vilnius.

Rafaelis Chvoles iš ciklo „Senasis Vilnius“. Vilniaus Didžiosios sinagogos griuvėsiai 1946 m.

Photo Credit: Paulius Račiūnas

|

The woodcarving tradition, inherited from generation to generation, acquires unexpected shapes in the piece by the early 20th century Jewish folk artist Aaron Chait from Kelmė – "The Throne of King Solomon". This masterpiece, created in the 3rd decade of the 20th century, is a multi-figural dimensional composition, a sculptural installation incorporating architectonic elements, carvings of different animals, and over two hundred dressed dolls. In the context of Lithuanian Jewish art this composition is unique. The traditional Jewish art in Lithuania has never used neither sculptural human groups, nor similar sculptural dimensional compositions, because of the strict understanding of the Second Commandment. No such compositions are known in the whole history of traditional Jewish art, either. Aaron Chait created this unusual piece to illustrate the biblical story of King Solomon’s court and his magical throne, described in Jewish legends. Unfortunately, due to the vast number of lacking parts, the authentic dimensional view of the composition is impossible to restore, thus the remaining objects are exhibited on a wall.

The Throne of King Salomon |

| For long time this unique piece of art, having no analogue in the history of Jewish art, – “The Throne of King Salomon”, created by Aaron Chait in Kelme in the beginning of the 20th century – was not known, although its constituent elements - wooden carvings, metal candle-stick, and puppets – were kept in the Vilna Gaon State Jewish Museum for a few years. This original work of art was preserved by Professor Paulius Galaunė, who, in 1941, among other exhibits rescued the wooden carvings, the puppets, and the metal candle-stick from the Jewish Ethnographic Museum, which functioned in Kaunas before World War II. After the war, the exhibits were kept in M. K. Čiurlionis Museum of Art in Kaunas, where nobody knew what these objects are and what is their purpose, because no records were left in the Jewish Ethnographic Museum. Later, in 1989, these invaluable exhibits were donated to the newly established State Jewish Museum (in 1997 renamed to The Vilna Gaon State Jewish Museum).

Because of their untypicalness and unusualness in the context of the traditional Jewish art, these exhibits were misidentified: the puppets and the carvings, parts of one entirety, were considered to be two separate works of Jewish folk art, and so the constituent elements of one composition were divided into two separate groups. A few years after this misidentification, the works were exhibited in The Vilna Gaon State Jewish Museum as puppets of Purim-shpil and as decorative composition of Aron ha-Kodesh. Recently, after a thorough analysis of these works it was established that in fact they are elements of a single composition, single indivisible piece of art, and both its plot and its author were identified as well. Explaining the plot of the work was aided by the main sources of the traditional Jewish art: Biblical texts and commentaries on the texts – aggadic literature, and description of the Salomon’s Throne in the Second Targum in particular. Attribution of the work was possible thanks to a memoir source – memoirs of Jaakov Chait, the son of Aaron Chait.  It turned out, that the wooden carvings, the puppets, and the metal candle-stick are elements of a single piece of art, called the King’s Salomon Throne, according to the story of Salomon’s Trial, and it was created by a Jewish folk artist from Kelmė Aaraon Chait in the beginning of the 20th century. The Salomon’s Throne is a grandiose spatial composition, consisting of many elements (carvings and puppets); in a way it is a model of the hall or palace of the Salomon’s Throne, created by Aaron Chait according to the description of the Throne in the Second Targum. The greater part of the Salomon’s Throne’s main carvings survives: the throne, flowers “growing” behind the throne, fifteen-branch candle-stick, which adorned the top of the throne, the main sculptural compositions of animals (various animals lying on stairs, and compositions of eagles-lions with extended wings and paws), some architectural motifs of the palace, etc. Very few puppets have survived – of approximately two hundred puppets we have only twenty three, but these include the greatest part of the main heroes of the Salomon’s Throne story: the High Priest, his assistant, seventeen members of the Sanhedrin, also half of the participants of the Salomon’s trial: a woman, a child, and a soldier, holding the child by his foot and ready to execute the sentence.      Unfortunately, we do not have the king Salomon himself, the second woman, the second child, many of the soldiers, and a great part of the members of the Sanhedrin. Almost a century after the creation of the Salomon’s Throne it turned out that this unique piece of art, searched by the son of the artist even in New York Metropolitan Museum (as he says in his memoirs), in fact still is in Lithuania, in The Vilna Gaon Jewish State Museum. Aistė Niunkaitė-Račiūnienė

Photo Credit: Paulius Račiūnas |

The memoirs of the artist’s son Jakov Chait who described it in detail, and the description of Solomon’s trial and Solomon’s throne in the Second Targum helped to reconstruct an approximate composition of the artwork.

In 1941 the remains of the majestic composition – about twenty-three human figures and part of the carvings – were saved from the destroyed buildingof the Jewish Ethnographic Society in Kaunas by the art critic Professor Paulius Galaunė. After the war the scattered composition was kept at the M. K. Čiurlionis Art Museum in Kaunas, where all that was known about it was that they were “Jewish dolls” and “Jewish carvings”. Later it was given as a gift to the Vilna Gaon State Jewish Museum. As the artwork’s authorshipwas lost, for many years no one even suspected that the “dolls” and “carvings” were part of a unique work of art. Only in the last decade when a thorough research of the surviving “dolls” and ‘carvings” was carried out and the memoirs of Jakov Chait were discovered was the story of this piece of art and the artist who created it revealed. Almost a century after “Solomon’s Throne” was created it turned out that the composition which the artist’s son looked for even at the Metropolitan Museum in New York, as he wrote in his memoirs, was really still in Lithuania, at the Vilna Gaon State Jewish Museum.

Dr. Aistė Niunkaitė-Račiūnienė

Encounters: Litvak Art of XX-XXI centuries

Encounters: Litvak Art of XX-XXI centuries

The 20th century was the time of great changes: new states emerged, empires crumbled, the old Europe was ravaged by wars. Progress in medicine, sciences and technologies determined the appearance of new artistic trends, as social changes and the challenges humankind was faced with influenced art trends too: modernism was born. Perfectly completed lines were not enough to express inner feelings and the traumas experienced during the wars. In visual arts futurism, constructivism, expressionism with searches for popular fauvism, expansion of colours, abstractionism that gradually grew into postmodernist art took the leading position. The renewed exposition “The Lost World: Encounters” devoted to visual arts displays works created by Lithuanian Jewish artists at the beginning of the 20th and the first decade of the 21st century. The collection was formed over the last several years by the Vilna Gaon State Jewish Museum, implementing its mission, which is to collect and preserve for future generations works by Litvak artist scattered all over the world or created in the homeland. The works by distinguished artists and their biographies show that many names connected with foreign painters and graphic artists are part of Lithuanian culture. Many of the artists (whose works are still sold at famous world auctions) studied at the Vilnius Academy of Art, while the artists of the older generation attended the Vilnius Drawing School, the J. Vienožinskis drawing school in Kaunas. Some artists received their first lessons in art at the Vilnius Ghetto (Samuelis Bakas) or hiding in a poky little room in Paris during the Second World War with no sunlight for almost two years (Theo Tobiasse).

The 20th century united several generations of Litvak artists, but they were separated by the war and the geopolitical changes that took place after it. The painters of the older generation Pinchus Kremegne (1890-1981), Emmanuel Mané-Katz (1894-1962), Isaiah Kulviansky (1892-1970) whose names are connected with the Vilnius Drawing School (1866-1915), left Vilnius in the inter-war period and joined the ranks of West European artists. Kremegne’s and Mané-Katz’ names are connected with the l‘Ecole de Paris art school, Kulviansky’s name with Israeli artists: he became one of the founders of the Palestinian Association of Painters and Sculptors.

The middle generation artists connected with Vilnius are Rafael Chwoles (1913–2002), Bencion Michtom (1909–1941) and Rachel Sutzkever (1904–1943), they were active members of the Jung Vilne, the Jewish literature and art association. The life of Michtom (a constructivist, follower of the Bauhaus art movement) ended in Paneriai, Sutzkever was killed in Treblinka, while fate gave Chwoles the chance to follow in the footsteps of some Litvak artists: he settled in Paris, but all his works have the same motif – Vilnius with its Old Town little streets white with snow or lit by the sun as they were in his childhood where he used to wander.

Černė Percikovičiūtė (1912–?) and Neemiya Arbit Blatas (1908–1999) were students at the J. Vienožinskis private studio, while the Kaunas art school that grew out of the J. Vienožinskis drawing course, educated our contemporary Augustinas Savickas (1919–2012), who later graduated from the Vilnius Academy of Art, as well as contemporary Lithuanian artists Adomas Jacovskis (b. 1948) and Solomonas Teitelbaumas (b. 1972). Rich pastose strokes in Teitelbaumas’ works were created already in the 21st century. They are very expressive, with loud colours that convey the feelings experienced while working. Jacovskis’ pictures are full of metaphysic feelings: a profile on a monocoloured background and a left hand with an index finger pointing at the sky (“Profile on a Blue Background”, 1990), or a singing herald in a red space (“The Hymn”, 1990), holding the shofar. The herald’s head thrown back and teeth send into space a soundless cry and the question “why?” that has tortured humankind throughout centuries.

The century separates and again brings together Litvak artists. Samuel Bak (b. 1933) although connected with the war time Vilnius, is at the same time our contemporary, who presently lives in Massachusetts. His paitings with many surrealist elements, metaphysic figure compositions with their illustrating language raise questions about the world in which we live, try to find answers to the duality of the human nature that caused the most cruel crime of the 20th century, the Holocaust.

At the exhibition, there is also a group of Litvaks, who beginning their artistic careers in Vilnius, later tied their lives with Israel: Isaiah Kulviansky, Yehezkel Streichman (1906-1993), and Moshe Rosenthalis (1922-2008). Theo Tobiasse (1927-2012) who was born to a family of Jewish immigrants in Israel should be attributed to this group. All of them have passed away, but are still among the most popular artists in Israel, who won state recognition and awards, influenced the art history of Israel (eg. Streichman, one of the founders of the New Horizons art movement). There is synthesis of painting and graphic in Rosenthalis’ works. His coloured lithograph “Composition with a Woman’s profile” is marked with a strong but disciplined line and several coloured patches, which makes the composition very expressive.

This text about the exhibition “The Lost World: Encounters” is just a light touch, several strokes trying to generalise the varied fates and works of 20th-century Litvaks who were scattered all over the world. Personal encounters and discoveries await visitors here, as well as during their wanders through the wide world‘s art galleries, suddenly reading the inscription near the biography of the artist: d‘origine lituanienne.

Ieva Šadzevičienė

Photo Credit: Paulius Račiūnas